I just came back from a 3-day marquetry class at the David Marks School of Woodworking, and although I am physically exhausted, I also feel creatively rejuvenated! Let me tell you about my experience there.

David and his wife Victoria are very friendly, down-to-earth people. They live in a modest house in the outskirts of Santa Rosa, a sleepy town located an hour drive north of San Francisco. David’s woodworking studio is located in the back of their property and offers 2,000+ sq-ft of space outfitted with a wide variety of power tools, workbenches, and even a complete drum set! (David’s band, appropriately named The Bench Dogs, practices in his woodworking studio. How cool is that?!)

David Marks’ claim to fame is to have hosted a television show named “Woodworks” on the DIY network between and, I was not terribly impressed by that since I started woodworking in, long after the show ended… I had only heard of David’s achievements through Marc Spagnuolo’s Wood Talk Online Radio podcast. Last year, for Christmas, my thoughtful wife gifted me a 3-day marquetry class at the David Marks’ School of Woodworking, prompting me to check out who the dude was. All I can say is that I was very impressed by both his craftsmanship and creativity. As a general rule, if you want to take a class with a master woodworker, look at the pieces of art that he or she has created. If you like their work, you’re likely to enjoy their company and benefit from the class.

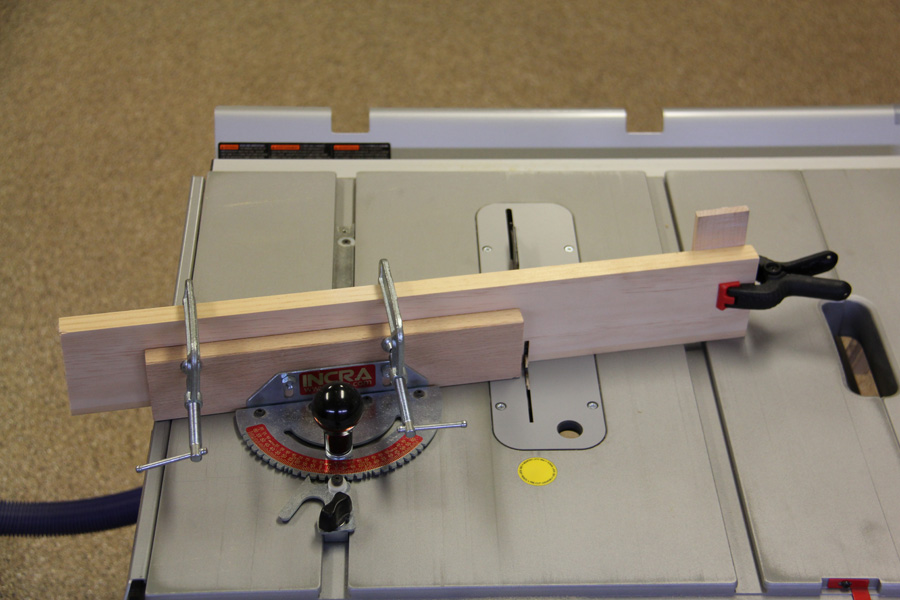

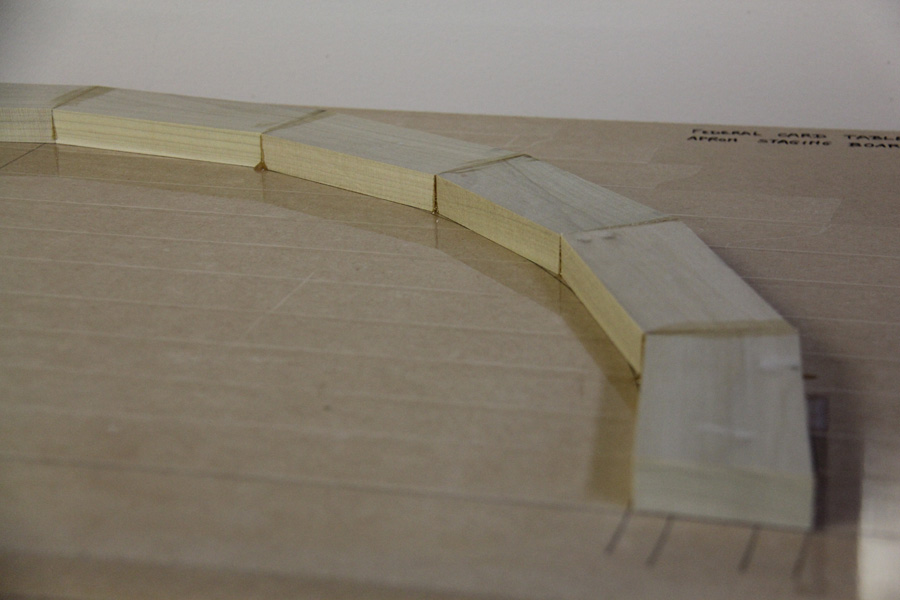

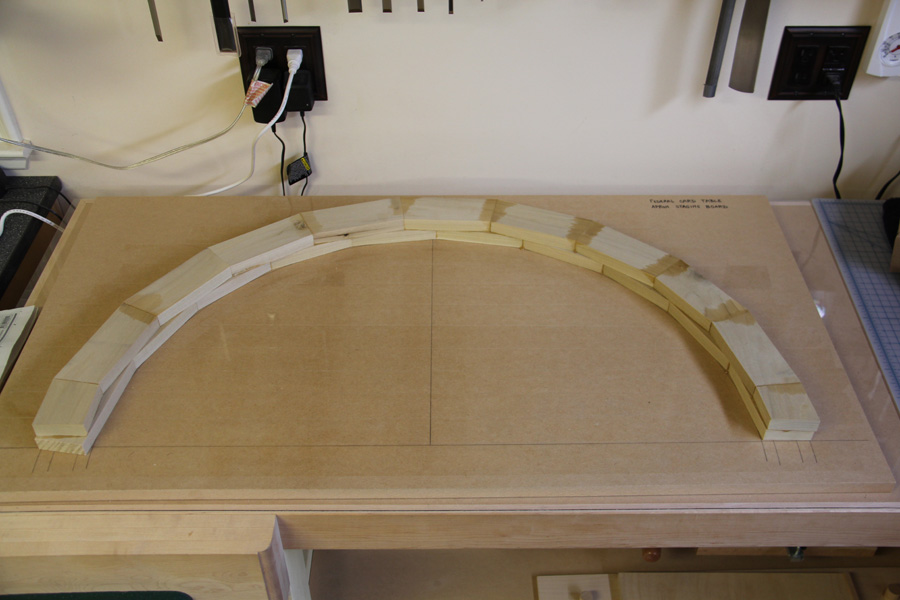

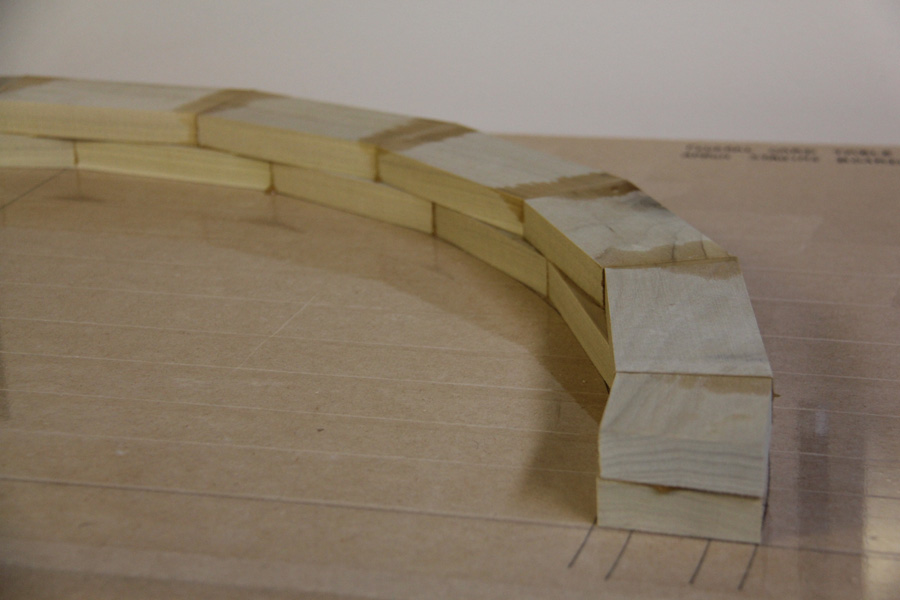

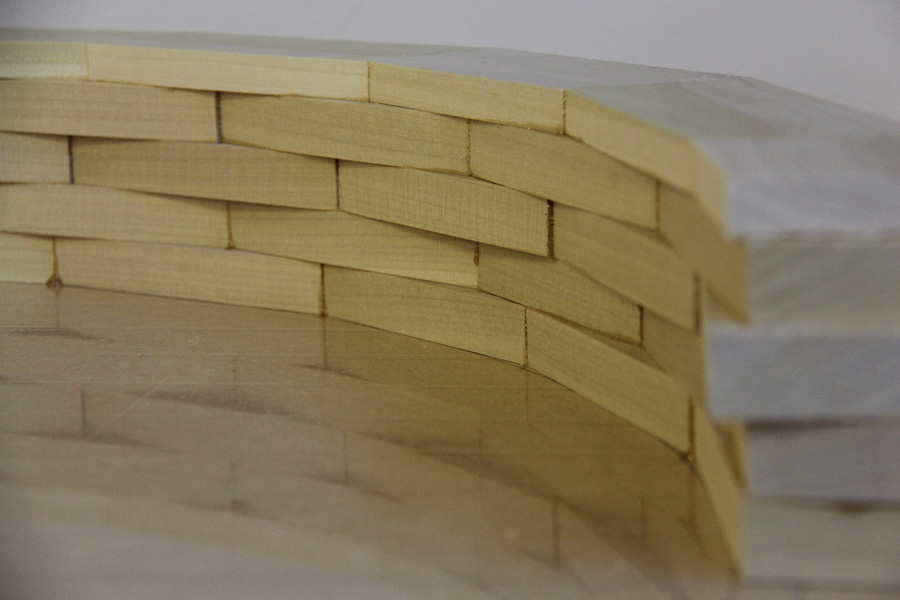

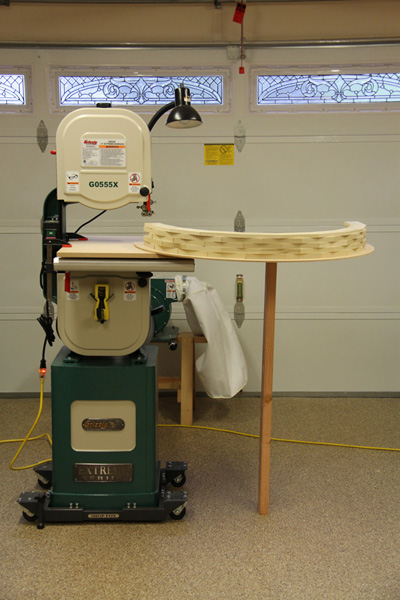

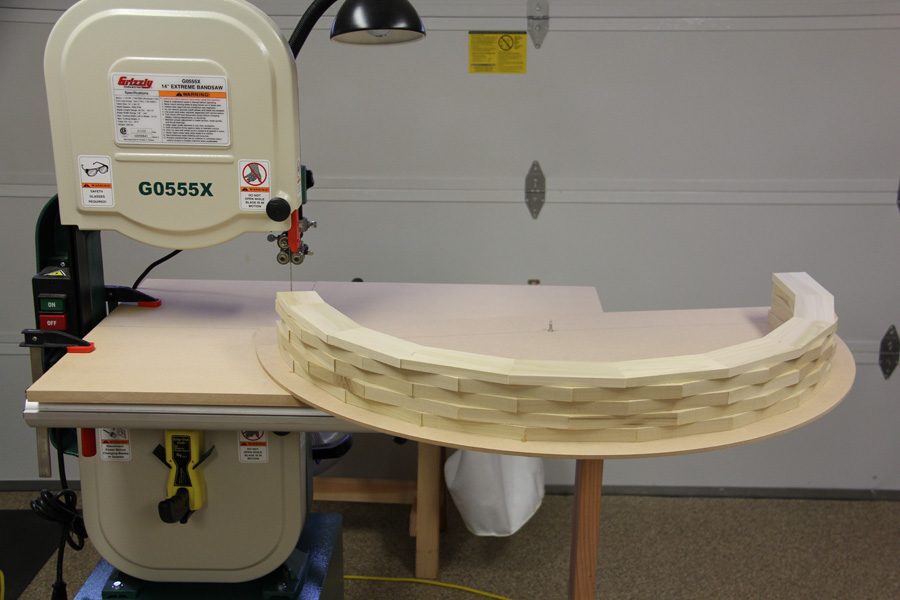

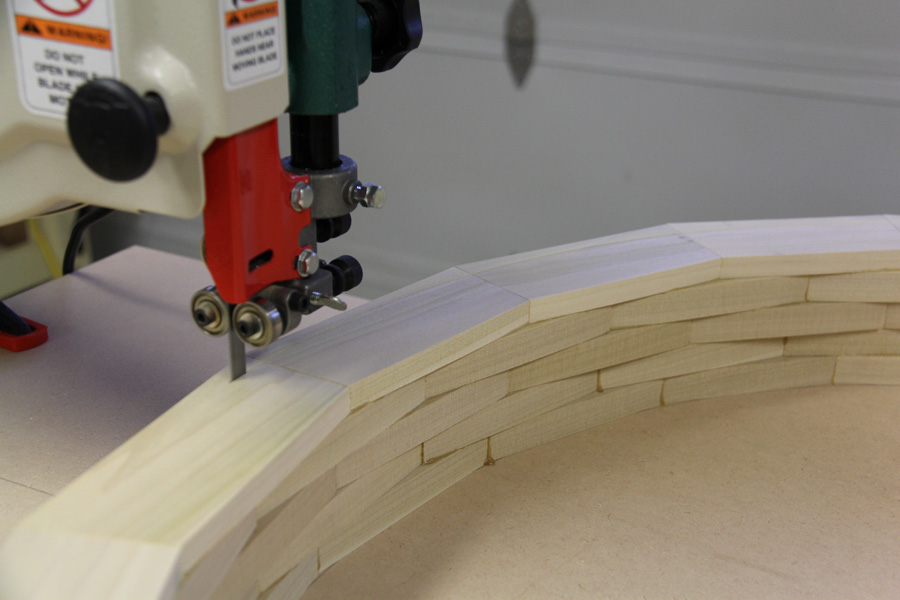

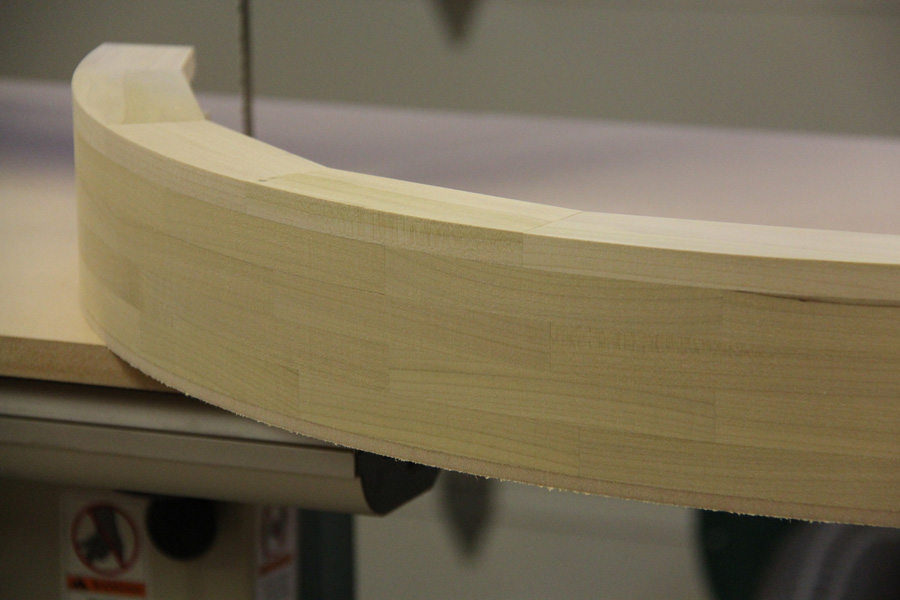

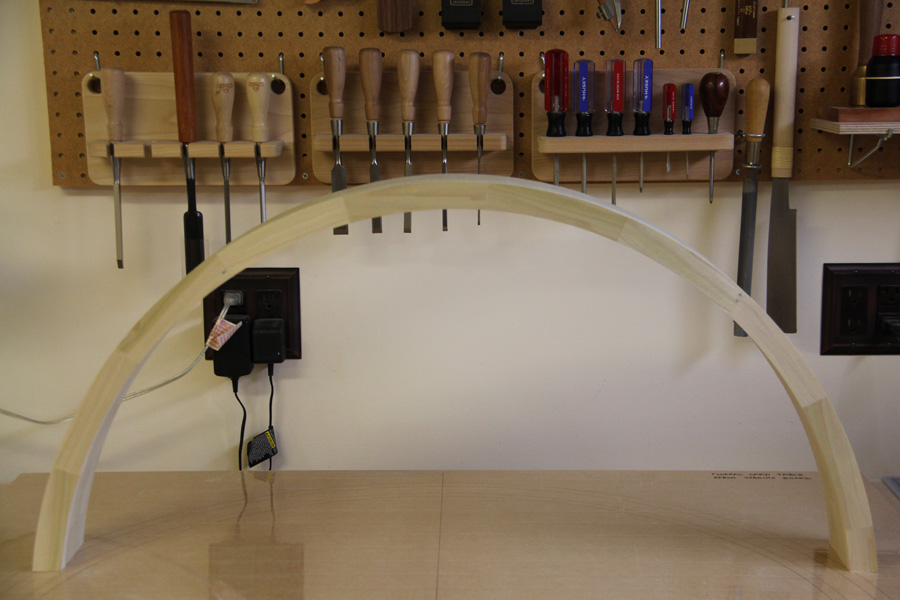

David remains very humble about his television show and instead lets his 30+ years of woodworking experience speak for itself. During the 3-day class, David took us through the process of making beautiful marquetry pieces using the double-bevel marquetry technique. He also demonstrated a lot of inlay techniques involving many different types of materials so that we could incorporate those into our work when the time comes. One of the best thing about the class was that we got plenty of hands-on experience and each walked away with a beautiful project. We all had our own scroll saw, and were able to use beautiful wood species that David had resawn into veneers on his own band saws.

David is very generous with his time. During the class, you can talk about anything even remotely related to woodworking, hear many stories and discuss the lessons that he’s learned about living his life as a free artist who cares more about his art and the quality of his craftsmanship than how much money he’s made or what kind of car he drives. This was very refreshing to me since I work in the high tech industry, a field notorious for its materialism.

Would I recommend this class? Absolutely! David is what I call an “approachable hero”. There are very few craftsmen like him left in the country, and being able to spend a few days in his woodworking studio was worth every penny! Also, if you’re not careful, you might even learn a thing or two :)

I am already planning to go back next year in order to learn more about wood turning (David is a world class wood turner, in case you didn’t know…) In the meantime, enjoy some of the photos from last weekend’s class below. Click on the thumbnails to see a larger version of each picture. The last one is a photo of my very own project :) Cheers!